Description

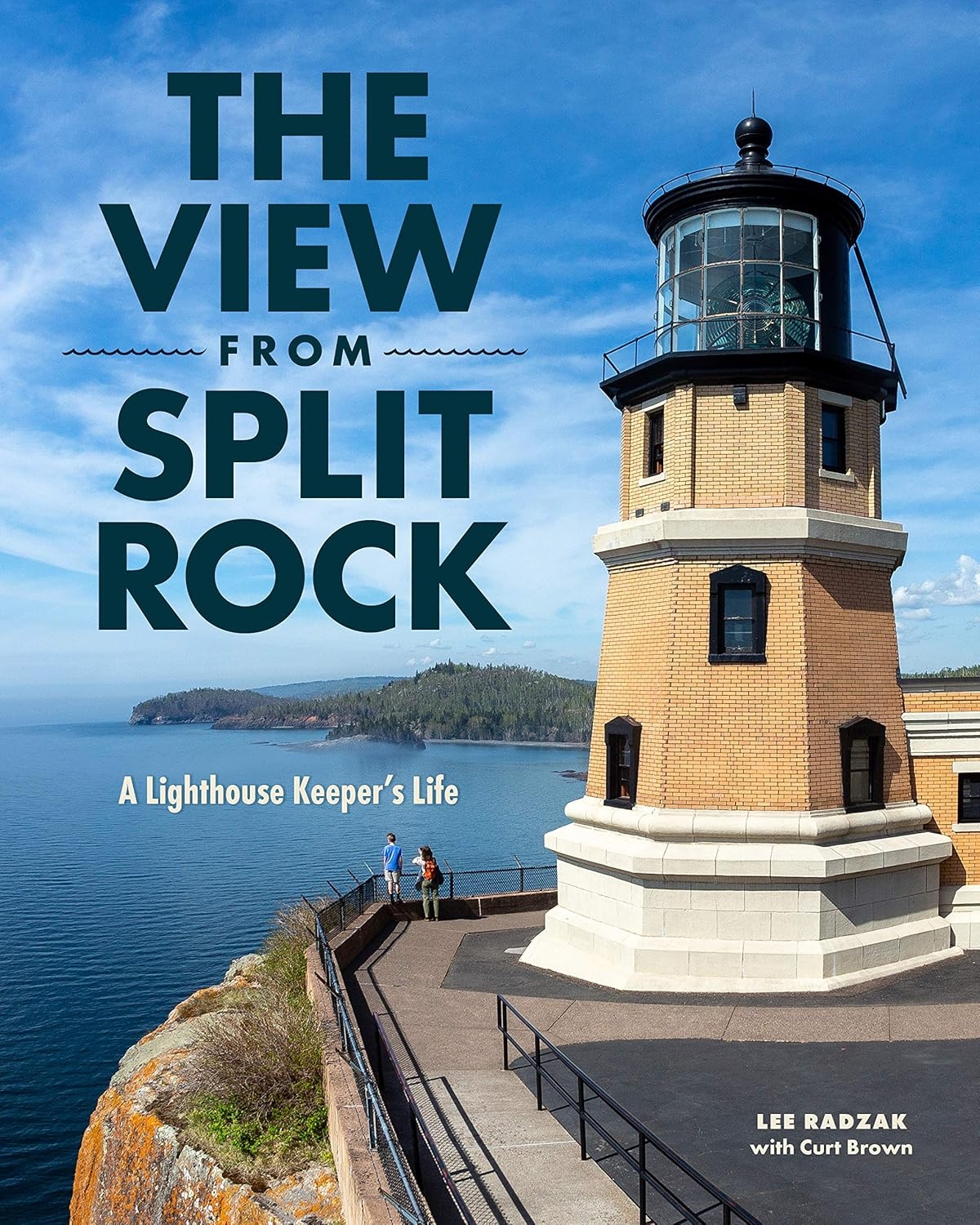

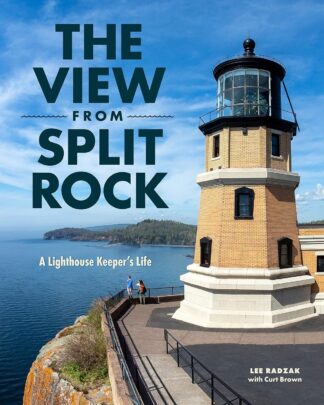

Split Rock Lighthouse is a Minnesota icon: a handsome structure perched atop a cliff on Lake Superior’s North Shore, gorgeous in every weather, a lonely outpost overlooking the vastness of the lake. Except that this lighthouse is not lonely. It’s one of the state’s most visited historic sites.

In 1982, Lee Radzak and his wife, Jane, moved into the middle keeper’s house at Split Rock Lighthouse, launching Lee’s career as the site’s resident manager. Over the next 36 years, they raised a family, marveled at the lake’s beauty, endured gigantic storms, and answered the questions posed by more than four million visitors.

Working with journalist and author Curt Brown, Radzak takes readers into the everyday experiences, the remarkable surprises, and the seasonal round of the life of a lighthouse keeper at Split Rock. He also discusses its construction in 1909, the technology that has powered the light and the foghorns, the stories of its keepers, and his decision in 1985 to light the beacon in memory of the crew of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Illustrated with pictures taken by Radzak and other talented photographers, this book offers a guide to and a stunning visual portrayal of life at Split Rock.

About the Author

Lee Radzak served for 36 years as the resident site manager at the Minnesota Historical Society’s Split Rock Lighthouse.

Curt Brown spent more than 30 years as a reporter at Minnesota newspapers in Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Fergus Falls. He writes a popular Minnesota history column every Sunday for the Minneapolis Star Tribune. Brown was named Minnesota Journalist of the Year in 2013 for his serial narrative on the U.S.-Dakota War. He is also the author of the book So Terrible a Storm: A Tale of Fury on Lake Superior, which chronicles a massive storm in 1905, and Minnesota, 1918: When Flu, Fire and War Ravaged the State. Brown lives near Durango, Colorado, with his wife, Adele.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

CHAPTER THREE: WINTER

The change to winter came slowly, in fits and starts. The days shrunk shorter, the shadows longer. Temperatures dropped with each new storm. The early winter days of November and December became the toughest to endure. This was the time of year when night arrived in the late afternoon and sunrise dawned slowly, waiting to emerge until after our breakfast. From my living room perch, I watched the dusk set in. I knew by heart exactly where the sun would set to the southwest on the winter solstice. At a few minutes after four in the afternoon on the shortest day of the year, it disappeared behind the shoulder of Day Hill―a prominent flat-topped basalt dome in the state park about a mile away. From late December on, I watched with great anticipation for spring. The sun set just a tiny bit further north each afternoon.

Most days, the sky was a solid leaden gray with low, thick clouds blurring the horizon. The light station was built on a point, so when you gaze south, east or southwest from Split Rock, Lake Superior meets that horizon. The big lake can make its own weather. Some days, the sky over the lake was fair while it was overcast and dark over the North Shore. On those days, the sun sparkled off the bright blue water like a billion diamonds. But that sun never climbed too high over the southern horizon―even at midday. On those short, sunny winter days, when I returned home for lunch, I liked to lie luxuriously on the living room floor with the dog as sunshine streamed through the south-facing windows. I caught a nap and some Vitamin D from the bright sunshine’s glow. A small dark silhouette of a Great Lakes freighter passed by, some fifteen miles out on the lake. Lit from behind by the low sun, the laker stood out in contrast to the bright lake. Many of these gigantic ore carriers were moving back and forth, loading taconite at the North Shore ports of Silver Bay, Two Harbors, and Duluth-Superior. They delivered as much tonnage as possible to the smelters down on Lake Erie. Fearing the big nor’easter lake storms, these ships hurried to fill orders for taconite before the Soo Locks closed for the season in mid-January at the eastern end of the lake.

Living at Split Rock, Lake Superior dominated both our lives and views as it surrounded us on three sides. The big lake’s presence was most notable during the winter months. I watched with fascination as the lake responded daily to the growing winds and falling temperatures. The surface temperature of Lake Superior warms all summer long and, because it’s such a vast body of water, it takes longer than the small inland lakes to cool as winter approaches. These warmer water temperatures at the lake surface help keep the shores around the lake warmer than the higher elevations rising away from the lake. It often snows just a mile or two inland in November and December, while along the shore we face a sloppy mix of rain and snow.

November marked a huge transition in Northland weather patterns. The warm, humid air coming up from the Gulf of Mexico gave way to polar winds howling down from the Canadian arctic. These two systems often clashed over Lake Superior. Massive low-pressure systems swirled out of the northeast, barreling down on Split Rock from across the lake. These storms often blew into sloppy two-day affairs with rain and snow blowing sideways before gale-force winds. These were the infamous “Gales of November” that wrecked many ships over the years―including the sinking of the 729-foot iron ore carrier Edmund Fitzgerald that went down with a crew of twenty-nine on November 10, 1975.

Details

- Publisher : Minnesota Historical Society Press (May 11, 2021)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 168 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1681341808

- ISBN-13 : 978-1681341804

- Item Weight : 1.19 pounds

- Dimensions : 7.9 x 0.6 x 9.9 inches

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.